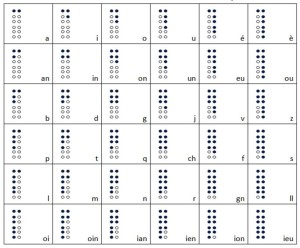

Charles Barbier de la Serre, France (1767-1841)

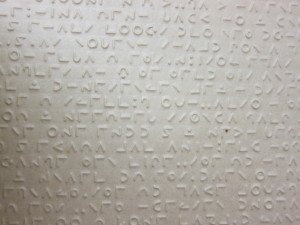

raised-point writing alphabet

Charles Barbier was the inventor of raised-point writing and the tools for creating it. In 1815 Barbier published “Essai sur divers procédés d’expéditive française”, a collection of proposed methods for writing letters or sounds that were intended for use by people who are blind or unable to use the existing written alphabet. He also created three tools for the creation of this writing system: a blunt punch to make the dots in the paper, a grooved rule to receive and space them out, and a movable guide to line up the dots vertically. He tested this system with several young children and inmates of a hostice for blind pensioners.

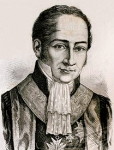

Charles Barbier

In 1821, Barbier wrote to the Institution Royale des Jeunes Aveugles (IRJA), where the director Dr. Alexandre-René Pignier assigned a senior student to learn the method and demonstrate it to the school’s board of directors. The students began to use raised point-writing of the alphabet as a means of writing and re-reading their own notes.

More information on Charles Barbier is available from Philippa Campsie’s excellent article “Charles Barbier: A hidden story“.

Louis Braille, France (1809-1852)

Louis Braille

Louis Braille was born on 4 January 1809 in the small French village of Coupvray. His father was a leather-worker and Louis was left blinded at age three after an accident while playing with an awl in his father’s workshop.

When he was ten, Louis was sent to the Royal Institution for Blind Youths in Paris. Charles Barbier’s raised point writing system and the tools for producing it were shared with the students in 1821. Louis Braille was excited by the idea as the dots were much easier to decipher and write than raised letters, however each symbol had too many dots to be felt with the fingertip at once. He proposed a number of changes that he incorporated into his own tactile code using a grid of just 6 possible dots in a 2 by 3 cell representing letters and punctuation. Louis Braille published the first braille book in 1829. In 1837, he added symbols for math and music.

Louis Braille died of tuberculosis at the age of 43 on 6 January 1853, just one year before braille was adopted as the official communication system for blind people in France. Contractions were added to the braille code after Louis Braille’s death.

You can learn more about Louis Braille in these two biographies:

- Louis Braille, a Touch of Genius by C. Michael Mellor. Available in hardcover print, hard copy braille and electronic braille from the National Braille Press.

- Triumph over darkness: the life of Louise Braille by Lennard Bickel

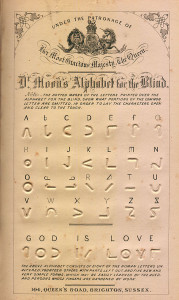

Dr William Moon, England ( 1818-1894)

Dr William Moon lost his eyesight at 21 years of age after being partially sighted throughout his childhood. He developed a tactile system for reading called Moon Type, which uses 14 characters with a clear, bold outline at different angles to represent the roman alphabet, numbers and common punctuation.

Dr William Moon lost his eyesight at 21 years of age after being partially sighted throughout his childhood. He developed a tactile system for reading called Moon Type, which uses 14 characters with a clear, bold outline at different angles to represent the roman alphabet, numbers and common punctuation.

The first booklet written in Moon Type, “The last days of polycarp”, was issued in 1847 while Dr Moon was working as a teacher at a school for blind boys. At first, Dr Moon produced his documents by hand at home, outside teaching hours. In 1856, with the support of Sir Charles Lowther, Dr Moon established a small workshop near his home in Brighton. This allowed him to mechanise the embossing process, using special printing plates. He later travelled widely, establishing libraries, home teacheing societies and printing presses throughout the British Isles and beyond. After his death in 1894, Dr Moon’s work was continued by his daughter, Adelaide.

Moon type was the first raised system of reading and writing used for teaching blind children and adults in Australia. It was replaced by braille as the predominant tactile writing system in Australia in 1874.

Moon type was the first raised system of reading and writing used for teaching blind children and adults in Australia. It was replaced by braille as the predominant tactile writing system in Australia in 1874.

Moon type is larger than braille and easier to learn and as such it has particularly been appreciated by people who lose their sight later in life. Documents in Moon type are still produced and distributed by the RNIB in the UK and the Queensland Braille Writing Association (QBWA) in Australia.

More information about Dr Moon and his alphabet is available from deafblind.com.

Henry Martyn Taylor, UK

Henry Martyn Taylor became blind in 1894 while engaged in the preparation of an edition of Euclid for the Cambridge University Press. He devised a braille mathematics notation using upper numbers, enabling him to transcribe many advanced scientific and mathematical works. The code was perfected in in 1917 with the assistance of Mr. Emblen, a blind member of the staff of the National Institute for the Blind. The Taylor code was recognised as so comprehensive that it was soon adopted as the standard mathematical and chemical notation in the UK and forms the basis of mathematics notation in Unified English braille with additional symbols. The Taylor Code was also used in the USA from 1946 until the introduction of the Nemeth code in the USA in 1952.

Rev. William Taylor, UK

The Reverend William Taylor became superintendent of the Yorkshire School for the Blind in 1836. While at the school he developed his “Ciphering Tablet”, first mentioned in the 1882 annual report of the British & Foreign Blind Association. The Taylor Mathematical slate was a device used in the teaching and working of mathematics for blind students. It consisted of a frame and a set of metal pegs or type with the patterns. The frame has rows of opening each set out as an eight-pointed star. The pegs could therefore be placed in the frame in one of eight orientations which could be used to represent numbers, letters or signs. Although difficult to master, it possessed several advantages over its main rivals which used raised numbers. Significantly less time was wasted in searching for the appropriate number. The Taylor slate was in common use until the 1970s.

The Reverend William Taylor became superintendent of the Yorkshire School for the Blind in 1836. While at the school he developed his “Ciphering Tablet”, first mentioned in the 1882 annual report of the British & Foreign Blind Association. The Taylor Mathematical slate was a device used in the teaching and working of mathematics for blind students. It consisted of a frame and a set of metal pegs or type with the patterns. The frame has rows of opening each set out as an eight-pointed star. The pegs could therefore be placed in the frame in one of eight orientations which could be used to represent numbers, letters or signs. Although difficult to master, it possessed several advantages over its main rivals which used raised numbers. Significantly less time was wasted in searching for the appropriate number. The Taylor slate was in common use until the 1970s.

The Rev. Taylor also went on to be one of the founders of the the College and the Blind Sons of Gentlemen at Worcester.

More information about use of the Taylor slate is available from the Commonwealth Braille and Talking Book Collective.

Hellen Keller, USA (1880-1968)

Helen Keller

Helen Keller was born in Tuscumbia, Alabama in 1880. At the age of 19 months, she became ill and was left both deaf and blind.

Helen Keller was the first deaf-blind person to earn a bachelor of arts degree in 1904. She went on to become a well-known author, political activist and lecturer. She wrote over 475 manuscripts, speeches and essays, all of which were prepared first in braille then copied using a regular typewriter. She was also one of the first members on the board of directors of the Permanent Blind War Relief Fund, now known as the American Braille Press.

In 1948 Helen toured Australia, visiting both the Sydney Industrial Blind Institution (Royal Blind Society) and the Royal Victorian Institute for the Blind (both now part of Vision Australia).

Helen Keller was a positive role model, demonstrating that people who are deaf-blind can participate to and make a meaningful contribution to society.

“The Story of My Life” is Helen’s autobiography, written in 1903.

Dr Abraham Nemeth, USA (1918-2013)

Abraham Nemeth was born in New York City. He was blind from birth. He attended public schools at first but got most of his education at the Jewish Guild for the Blind school in Yonkers, New York.His first love was mathematics, but his vocational counsellors all told him that there was no future in that career.

Dr Nemeth’s undergraduate studies were at Brooklyn College where he read psychology and graduated in 1940. He took mathematics electives wherever he could. He earned a Master of Arts degree in Psychology from Columbia University in 1942 but struggled to find related work. He studied more mathematics taking electives and night classes, and by 1946 started doing casual work in tutoring and fill-in teaching. In 1955 he was appointed to the University of Detroit where he taught mathematics and computer science for the next 30 years, eventually becoming a full professor.

Meanwhile, in 1950, Dr Nemeth enrolled for a Ph.D. in mathematics—which he eventually obtained in 1964. As his mathematics studies blossomed, encompassing new topics and higher levels, he became dissatisfieed with the Taylor code for mathematics (1917) that he had been taught. He instead devised his own notations and maintained consistency between subjects. In 1952 the first edition of the Nemeth braille code for mathematics and science was published. The code remains highly-regarded and in wide-spread use today.

In 1991 Drs Tim Cranmer and Abraham Nemeth considered the desirability and feasibility of developing a more unified braille system. They made a passionate and logical call for harmonisation between the literary and technical codes used in the United States. BANA responded by establishing a research project to develop proposals for extension of the literary code to harmonise with technical codes. This work has culminated in Unified English Braille, now adopted by all eight member countries of the International Council on English Braille.

Dr Nemeth is best known for his development of the Nemeth code. He also developed the rules of MathSpeak, a system for orally communicating mathematical text. In the course of his studies, he found that he needed to make use of sighted readers to read otherwise inaccessible math texts and other materials. Likewise, he needed a method for dictating his math work and other materials for transcription into print. The conventions he developed for efficiently reading mathematical text out loud have evolved into MathSpeak.

Further information about Dr Nemeth and his work is available from the American Printing House for the Blind (APH) Hall of Fame and his obituary in the “New York Times”.

Dr Tim Cranmer, USA (1925-2001)

Tim Cranmer was a blind inventor, referred to as “the Thomas Edison of the blind”, with a passionate belief in the importance of braille literacy.

Self-educated after completing sixth grade at the Kentucky School for the Blind, Tim Cranmer worked as a piano technician, pianist, and workshop worker before devoting thirty years to Kentucky Rehabilitation for the Blind from 1952 to 1982.

Dr Cranmer went on to found the International Braille Research Center for research into the creation of graphics that can convey information to blind people with the most detail and least clutter. He also brought the research and development arm of the National Federation of the Blind into being.

Dr Cranmer was a prolific inventor. Some of his most prominent innovations included:

- A modified Perkins Braillewriter that was the first electronic braille printer.

- The Cranmer abacus, a modified Chinese abacus with felt backing to prevent the beads from moving by themselves. Thousands of these devices are still sold by APH each year for use by blind students undertaking mathematics.

- Audio/tactile braille displays for use with clocks, stopwatches, clinical system monitors, etc.

- A braille font with tactile graphics for use with the Pixelmaster.

- The Speaqualizer Speech-Access program, one of the first effective screen readers.

- Major contributions to the electronic circuitry and design for the Braille ‘n Speak and the Braille Lite.

Dr Cranmer was also instrumental in the initiation of Unified English Braille when, in 1991, he and Dr Abraham Nemeth wrote a memo to the Braille Authority of North America calling for a general purpose braille code to reduce the complexity and disarray caused by multiple codes for literary, math and computer text.

Dr Cranmer was recognised for his achievements, receiving an honorary Doctorate of Applied Sciences from the University of Louisville in 1979; an Outstanding Service award from the National Rehabilitation Association; the Neil Pike Award for Distinguished Service from Boston University; the Susan B. Rarick Award for Outstanding Service to Blind Men and Women from the NFB of Kentucky and the Louis Braille Award from the International Braille Research Center for his advancement of Braille research, production, and literacy.

More information is available in Dr Cranmer’s obituary in “The Braille Monitor”.

The Australian Braille Authority is a subcommittee of the Round Table on Information Access for People with a Print Disability Inc.

The Australian Braille Authority is a subcommittee of the Round Table on Information Access for People with a Print Disability Inc.

Last updated: June 5, 2024 at 19:29 pm